Muhtar Kent's New Coke

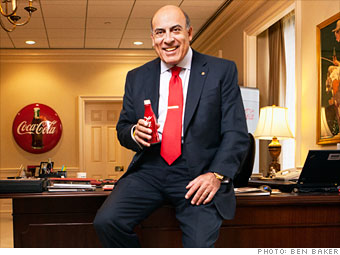

Kent, photographed in his office at Coke's Atlanta headquarters on April 20. Photo: Ben Baker, Fortune

This unflagging confidence that China will more than double its sales of Coke products to leapfrog Mexico and the U.S. and become the company's No. 1 market confirms what many investors (and millions of consumers) have come to realize: Kent has put Coke (No. 59 on the Fortune 500) back on track -- after years of mismanagement -- and he's set up the beverage giant for significant growth around the world.

Since he ascended to the CEO job in July 2008, he's redefined Coke's culture and replaced about 70% of its senior managers, filling the ranks with operators who, he says, "know how to generate results." The new team has ramped up spending, energized Coke's marketing efforts, and cranked up the dealmaking machine: The company is discussing a potential partnership or possible investment in energy-drink maker Monster Beverage. Coke has been busily integrating its $4.1 billion purchase of Glacéau's Vitaminwater, and Kent personally devised an intricate $12.3 billion deal that restored company control of its bottling operations in North America and positioned Coke to ignite growth in a once-stagnant market. The upshot: Revenue last year soared 33% to $46.5 billion, in part because of the bottling deal, and operating profits rose 20% to $10.1 billion. The stock is up 48% during Kent's tenure while the S&P has risen 10%. Shares of rival PepsiCo (PEP)? Up only 5%

Coke (KO) and Pepsi perpetually seesaw; when one is up the other is down, an uncanny pattern that seems destined to continue. Right now it's Coke's -- and Kent's -- time. Coke is the No. 1 soft drink in the U.S., and Diet Coke has surpassed Pepsi as No. 2 in the category. Coca-Cola has built 15 billion-dollar brands, including Sprite, Fanta, Minute Maid, Powerade, and Dasani water. While PepsiCo investors are critical of Indra Nooyi's performance, Coca-Cola's shareholders and directors are feeling content. Herbert Allen, the CEO of investment firm Allen & Co., calls Kent "the best chief executive Coke has had in 25 years."

Now Kent aims to double Coke's business by 2020, no small feat for a company on track to hit $48 billion in sales this year. To achieve that ambitious goal, he is pushing Coke to be more global, agile, and entrepreneurial -- in essence, more like himself. "I've never met anyone so intense," says Coke board member and IAC chief executive Barry Diller, who is buying Coke stock for the first time. During a nonstop, five-day trip through Asia in late March, the 59-year-old Kent constantly exhorted his employees and managers to act with urgency. "This is your once-in-a-lifetime opportunity," he tells them. "Don't miss it."

Muhtar Kent says he is constructively discontent. It's day one of the trip through Asia (Coke is letting me tag along), and Kent and I are having breakfast in Bangkok -- coincidentally, the first home he recalls from childhood, when his father was Turkey's ambassador to Thailand. I ask Kent what "constructively discontent" -- his preferred description of his leadership -- means exactly. "Not fast enough, not innovative enough, not entrepreneurial enough," he replies. "It's all about an entrepreneurial mentality. I've worked religiously to get that into the company."

Injecting entrepreneurial religion involves getting Coke's 146,000 employees to think like owners. "People need to feel like they are chasing pennies down the hallway," says Kent, who has been known to roam the 25th floor of Coke's Atlanta headquarters and turn off lights when he works late. At Kent's Coke, managers must pay $15 monthly if they use their cellphones for personal calls. (The rule applies to the CEO too.) He believes that one of Coca-Cola's problems was -- and America's problem still is -- lack of respect for cash. "When you don't see cash, all sorts of things go wrong," he says. "You overspend as an individual and overspend as a company." The CEO pays cash when he fills his BMW at the gas station. When I ask him how much cash he has on hand he pulls out a money clip and counts $181. In fact, the only currency Kent doesn't monitor seems to be Coke stock. The CEO tells me that he looks at the share price only once a week.

Kent has been Coca-Cola's resident entrepreneur almost since he joined the company in 1978. He started in bottler operations in Atlanta after graduating from the University of Hull in England and lasting seven weeks in a job he loathed, at Bankers Trust in New York. He got promoted to a marketing job in Rome, only to hear rumors that Coke planned to shut the Italy office. Kent flew to London and worked out an assignment to sell Coke to European airlines, trains, and ships. "It was the perfect entrepreneurial job," says Kent, who kept an office in Amsterdam, "just me and a Dutch secretary, Agnes." Figuring that Coke's standard 12-ounce cans were too unwieldy for the small galleys on planes and the like, Kent found a manufacturer to make 150-milliliter mini-cans. Coke captured major accounts across the Continent.

By age 32, Kent was running Turkey for Coke -- and soon known across the company for increasing "per caps," or per-capita consumption levels, in his markets. Kent had his own once-in-a-lifetime moment after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. Neville Isdell, Kent's boss at the time, put him in charge of Eastern and Central Europe and told him, "I want to take risks. Do things that have never been done before." Kent remembers flying to Atlanta and telling his bosses, "I need capital, and we've got to go now." Kent and his team built 22 factories in 28 months.

Kent distinguished himself by lavishing attention on the independent companies responsible for packaging and distributing Coke's beverages around the world. "I was staggered by his focus on the needs of the bottlers," recalls Don Keough, president of Coke from 1981 to 1993. Kent had good reason to maintain good relationships with these partners. Coke manufactures concentrates and syrups, but the bottlers are closer to the customer; they make, sell, and deliver the drinks.

Coke management at the time had other ideas. Doug Ivester, who led Coke after the 1997 death of legendary CEO Roberto Goizueta, sought to maximize Coke's own profits by strong-arming bottlers to consolidate and also overcharging them for concentrate. The moves alienated bottlers and left them financially strapped.

Kent experienced all this firsthand. In 1995 he became the European chief of Coca-Cola Amatil, a big Australia-based bottler. He was so disgusted and worried about Coke's actions that he decided he would quit. He ended up resigning, but for a different reason. Kent got caught in a stock-trading incident after his broker sold short 100,000 Amatil shares in advance of a profit warning. Kent settled the case in 1997, gave up the profits he had made, and denied wrongdoing. "I should have been more careful," he says today, talking publicly about the incident for the first time. "That taught me a lesson that you should never take anything for granted."

Bruised and also determined to control his destiny, Kent returned to Turkey, set up a consulting business, and soon accepted an offer to head Efes Beverage Group, an Istanbul-based brewer. Kent loved his six years at Efes, expanding in soft drinks -- he opened Iraq's first Coca-Cola plant -- and creating new products like Stary Melnik, which grew to become a top-selling beer in Moscow.

Kent never lost touch with Coke, which struggled mightily in the late 1990s and the first half of the 2000s. Ivester, the financial engineer, lasted less than three years as CEO. He was succeeded by Doug Daft, another finance man whose mercurial style alienated some of its best talent before he was pushed out. But Kent had no interest in returning to the company, even when, in 2004, he got a desperate call from his old boss, Isdell, who had been coaxed out of retirement to become CEO and stabilize the company. "I can't do this without you," Isdell told Kent time and again. The Coke board questioned whether Kent's stock-trading controversy would preclude his rehiring. Six months passed until everyone agreed on terms, including Kent's: "I said I'd come back with one caveat," he recalls. "I told Neville, 'I've never worked in Asia. I want to be connected to China.'" Why was he so adamant? "Because you want to do new things in life," Kent says.

Kent returned to Coke in 2005, as head of North Asia, Eurasia, and the Middle East. He followed his old playbook, working with the bottling network to find ways to boost sales volumes. When Isdell promoted him to president of international operations, and then of the entire company, Kent zeroed in on fixing Coke in the U.S. The problem, in a nutshell: Coca-Cola Enterprises, which was Coke's biggest bottler and a tarnished remnant of Ivester's financial strategy, had taken on too much debt and could not invest adequately in Coke's brands. "Coke had no chance to grow in the U.S.," Kent believed. Isdell agreed -- and tried unsuccessfully to buy CCE's North American business, twice.

Then Kent found his potential linchpin for a deal in June 2007, over breakfast in Madrid with Steve Cahillane, the president of Labatt USA. CCE chief John Brock wanted to recruit Cahillane to head CCE Europe, but Kent saw Cahillane as the ideal executive to turn around Coke's U.S. business. (Cahillane was an entrepreneur too. He founded State Street Brewing in the '90s, which impressed Kent.) Kent encouraged Brock to put Cahillane in charge of CCE North America. Relations between Coke and CCE improved dramatically. Then, in 2010, Kent sold CCE and the Coca-Cola board on a megadeal to buy the North American bottler. The complex agreement required Coke to pay $12.3 billion and give CCE rights to bottle Coca-Cola products in Norway and Sweden. "It was Muhtar's excruciatingly detailed plan that convinced the board to proceed," says Diller.

Since the acquisition, Kent's Coke is bigger and more complicated than the Coca-Cola Co. led by his predecessors. The deal brought 65,000 new employees, $21 billion in revenue, and various synergies that helped Coke slash $350 million in annual costs at the same time that commodity prices were spiking and squeezing the company's profits. "Had we not done the CCE deal, it would have been cataclysmic," Kent says. While Wall Street fretted that owning the big bottling unit would crush Coke's high returns on capital, veteran analyst Caroline Levy of CSLA Crédit Agricole Securities approves of the strategy: "Buying CCE wasn't good for the short term, but it is exactly right for 2020."

The complexity of Kent's Coke would seem to hamper his scheme to make the beverage giant more nimble and innovative. But Coke's aggressive acquisitions of independent brands such as Honest Tea, Zico coconut water, and Innocent, a British-based juice, have infused the company with entrepreneurs who continue to run their brands and in many cases operate far from corporate headquarters in Atlanta.

Kent has simultaneously filled his ranks with executives who share his constructive discontent. Derek van Rensburg, president of venturing and emerging brands, is constantly pushing Coke to buy more niche brands. "All he does is knock on my door and create havoc," Kent says proudly. David Butler, a shaggy-haired design guru whose title is vice president of innovation, led the design development of Coca-Cola Freestyle, a self-serve fountain machine that lets consumers mix their own beverages via touchscreen. (Anyone for Vanilla Coke Zero + Hi-C Orange?)

Marketing, which foundered under previous leadership, took on a new urgency in Kent's Coke. He helped recruit Wendy Clark, 41, from AT&T (T) four years ago and soon put her in charge of digital strategy. She has built the largest consumer-brand fan page on Facebook, with 41.4 million "likes." The key to building brands on Facebook, Clark says, is letting the fans take control, a risky proposition for a corporation that has fanatically protected its brand. Clark and her team sat back and watched while two avid Coke drinkers named Dusty Song and Michael Jedrzejewski built a fan page. After they had aggregated 1 million "likes," Clark invited the two guys to Atlanta, gave them a tour, shot a funny video, and sent them home with Coke bling. Keep on doing what you're doing, she told them. "We need to embrace our new sales force," she says.

To home-grow the next generation of innovative leaders, Coke has launched a program called Talent 2020. At first blush it sounds like a typical management training program for high-potential executives. They're assigned to research a challenge outside their area of expertise. But six months later they pitch their findings to Kent and his leadership team, sans props such as PowerPoint presentations. "Talk to me," Kent says. "Look me in the eye." Strong ideas actually get implemented: Ben Deutsch, the company's communications VP, recommended digital and social media training companywide. Today every employee must take a 30-minute online course on the subject.

Of course, for all his talk of agile management and innovative thinking, Kent can never lose sight of the fact that he is stressing an enormous enterprise. Any new product, no matter how entrepreneurial its roots, adds complexity: New packages -- such as 1.25 liter Coke targeted at moms and 89¢ Coke Zero designed for teenage boys -- help lift Coke's volumes in the U.S., but they require Coke to work with its elaborate network of bottlers, retailers, and other partners. "It's value-added complexity," says Sandy Douglas, the president of Coca-Cola North America.

All the more reason that Kent needs to communicate a clear vision to Coke's employees. His plan to double sales over the decade, dubbed Vision 2020, is modeled on McDonald's (MCD) CEO Jim Skinner's one-page "Plan to Win." Kent's vision is long-term, but his message is urgent around the world: "There is no tomorrow without today." It's a message he delivers to government leaders as well. "The future of the world belongs to two groups: those that can grow and those that cannot grow," Kent says. "Those that don't grow will go into oblivion."

The CEO has plenty more to do. He is off to India in June to open a retail sales center. He is eyeing opportunities in Burma, one of three countries where Coke currently doesn't sell its drinks. (Cuba and North Korea are the other two.) He is driving a program called "5 by 20" to empower 5 million women entrepreneurs globally by 2020.

Kent doesn't have to keep doing any of this. Traveling through Asia with him, I sense he could be just as happy focusing on being an entrepreneur -- he has a tiny olive oil startup in Turkey. When I ask the CEO how long he plans to stay on at Coca-Cola, he tells me that he doesn't know. "Psychic income is key," he says, smiling.

He has upgraded Coke's succession planning. Of course, he won't reveal who might lead Coke someday. But Cahillane, whom Kent calls "a no-nonsense operator," is clearly a strong candidate. José Octavio Reyes, Coca-Cola's Latin American president, is too. Also on the board's radar: Brian Kelley, a Kent recruit who ran Lincoln Mercury at Ford (F). Kelley, who also worked at General Electric (GE), earned praise for directing CCE's integration into Coke.

When I ask Diller if he expects Kent to stay to complete his Vision 2020, the Coke director answers: "Are you kidding? How about 2040? He gets better every year." Diller says he never bought Coca-Cola stock until three years ago, after Kent became CEO. He now owns about 2 million shares.

While Diller and other stockholders probably know the value of a Coke share, Kent opts to get that information in a weekly report. This is an odd habit for a Fortune 500 chief, but this CEO in a hurry seems to prefer to spend his days meeting employees and exploring those rare new territories. "Looking at the stock," he tells me as we check out a Chinese retailer's Coke display, "is just a loss of time."

This story is from the May 21, 2012 issue of Fortune.

Last modified onSaturday, 06 May 2017 10:07

Tagged under

Latest from Admin TOA

- 300 migrants to be housed at shuttered Catholic church on Northwest Side in Chicago

- Turkish Stand-Up Sensation Hasan Can Kaya Embarks on U.S. Tour with Art Evi Production, in212 Production, and TAAS New York

- "Lean Startup, To Lean Company, To Rich Exit" by Dr. Kenan Sahin is released with Forbes Books

- LOSEV USA Ramadan Campaign Let the Children Heal First with Your Ramadan Donations

- Azerbaijan Society of America Honors Centennial Anniversary of the Great Azerbaijani Politician the National Leader of Azerbaijan President Heydar Aliyev