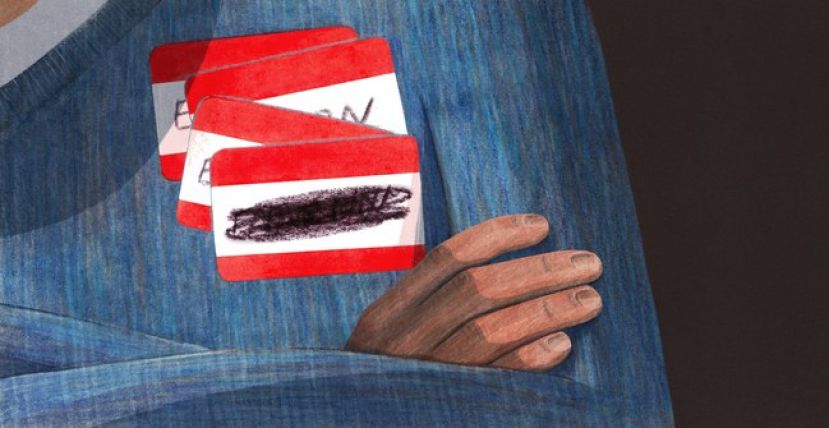

Solving the Problem of My Turkish-American Name

By Eren Orbey - The New Yorker - Translated into English, my mother’s name means “joy”; my late father’s, “handsome”; my sister’s, “mystery.” In my family’s native Turkish, the name chosen for me, Erin, means absolutely nothing. My parents, chemical engineers who immigrated to the United States, mistook it as a boy’s entry in a book of baby names. They thought that they had discovered an appealingly Americanized version of Eren, a traditional Turkish name that means “saint.” But like many ill-fated hybrids designed for dual objectives—the spork, say, or two-in-one shampoo-conditioner—my birth name failed to perfect either; most Bostonians assumed that it belonged to an Irish girl. So, to amend this misunderstanding before the bullies abused it, my father rechristened me, unofficially, with the first name of his favorite composer, Aaron Copland. “Personally, I have always preferred Tchaikovsky,” my mother told me not long ago. “But we were not going to call you Pyotr Ilyich.”

Perhaps they should have. I’ve often wished that my parents had picked a more definitive name, something like Timur—“iron,” in Turkish—which Americans might admire as “ethnic” before truncating to the more manageable Tim. The contradiction between Erin, on paper, and Aaron, in person, offers nothing but confusion. When I travel, often with friends who have unthinkingly purchased group airfare for their male pal, T.S.A. agents balk at the mismatch between my ticket and passport. When I order coffee, diligent baristas read the legal name on the receipt and withhold my lattes for a woman who will never arrive. Once, dining out with my beautiful friend Caroline, I watched a waiter march off with our credit cards, somehow incensed by our unromantic decision to split the bill. Moments later he returned, slicking back black hair and dismissing me with no more than a glimpse. He pulled a red Visa and its receipt from the check presenter, registered a female name, and turned, at last, toward my tablemate. “Erin,” he said, handing Caroline my credit card. “That’s a gorgeous name.” Then he took a long look at me: “You pay for a lady, sir.”

A perfect name may be too much to ask. Many people, I imagine, deal with far worse than mine. Rather than pout, I’ve tried to sympathize with the cynics saddled with virtue names like Faith and Chastity, or with the daughter of my grade-school teacher Mr. Day, whom he named—with a sincerity that stunned me even then—Summer. Still, it has occurred to me, as I near the end of college, that if I ever want to claim a new name—something to call my own, with neither reservation nor regret—then I probably should not wait. With this mission in mind, I decided to visit the drab, forbidding bowels of a probate court, where I waited for someone named Chantal to return from her lunch break and supply the necessary paperwork. I was done with my name and determined to change it.

To be renamed in my home state of Massachusetts, as in many others, a petitioner must swear that he is eighteen years or older and that his purposes are not defamatory, unlawful, or inconsistent with the public interest. (They can still be frivolous: in 2012, a budding Nebraskan entrepreneur changed his name to Tyrannosaurus Rex, stating in his filing that “name recognition is important.”) The filing fee is a hundred and sixty-five dollars, the surcharge another twenty, and, should the court in the petitioner’s county require public notice of the decree in a newspaper, that citation costs fifteen dollars more. Besides the page-long change-of-name appeal, the sole identification required is a certified copy of the petitioner’s birth certificate. Then the court requests a criminal-record check from the Office of the Commissioner of Probation and, upon its approval, sends the case to a judge who, barring objections, accepts the change and signs a certificate to legalize the new name.

The process was even quicker a century ago, when European shipping agents simplified the names of many settlers boarding barges westward. (Contrary to common lore, officials at Ellis Island rarely outright changed immigrant names but often transliterated them—from Cyrillic script, for instance, into the Latin alphabet.) This trend resulted in the mass transmutation of many Jewish surnames: Kaplan into Copeland, Lifshitz into Lipton. The reasons to Anglicize were evident then: better business, swifter assimilation. In the twenty-first century, the application for naturalization now lets immigrants change their names by checking a box, but, according to a Times report, the practice had actually declined by 2010. Today, the vast majority of petitioners for renaming file as a result of marriage rather than prejudice—though one wonders whether, under President Trump’s nativist Administration, newcomers might once again feel pressured to surrender their foreign names.

Neither of my own names has posed as many problems as those of my family members. When, early in the nineties, my newly immigrated parents deposited my sister in an American preschool system, they were condemning her, though they did not know it then, to more than a decade of derision. Gizem (pronounced gi-zem), a common Turkish name today, was fairly rare when my mother first chose it, in Ankara. It was even rarer in America. On the playground, the unfamiliarity of my sister’s name conspired with more overt foreignness—she could not speak English—to estrange her from classmates with names like Megan and Kate. What merely estranges someone in elementary school ends up marking her as a target in junior high, where the crudest students delighted in mispronouncing the first syllable of my sister’s name with a soft “G.” In time, kinder classmates settled on the more affectionate and phonetically fitting nickname “Gizmo,” but this choice still irked my mother, who suspected that it was teen-age slang for something nefarious.

An American name is an important asset: this has long been my mother’s refrain. My father’s originally Arabic name is Hasan (pronounced huh-suhn), which she always considered too traditional for her progressive, secular husband. He died before 9/11 but would, one imagines, find himself detained in today’s airports with such a name. Had my mother, Neşe (pronounced neh-sheh), not already published articles under her birth name, she probably would have changed it upon naturalization. Lately, to avoid confusion, she has taken to introducing herself simply as “N,” which her accent converts into an American name. People hear “Anne,” and that is what they call her.

When I informed her that I had decided to change my name, my mother assumed that I had settled on Aaron. It is, admittedly, a tempting option, boasting perks like alphabetical primacy while eliciting no cumbersome questions. Of course, it has never quite felt like mine. Erin, meanwhile, because of its feminine bent, remains equally foreign. My mother has explained that its crucial root is er, which, in Turkish, means “man”—as in “soldier,” she specified, whose translation is asker. But I cannot shake another online definition that lists my birth name as the second-person imperative form of the Turkish verb erinmek, which means “to be too lazy to do something.” (“I have never heard of such a verb,” my mother told me, appalled.)

Her greatest fear is that if her son changes his name she might lose him. It’s an irrational impulse that I nonetheless understand. She has already lost her husband, and, unlike him, I am indeed more American than Turkish—a perfect candidate, perhaps, for Aaron. Besides, in abandoning one name-related annoyance, am I really going to introduce myself to decades of new logistical snafus and clumsy mispronunciations and repeated demands to spell that out, please? Eren, stressed on the second syllable, may still sound female—and will certainly sound foreign—to most Americans.

I had never seen my mother so exasperated about a matter that seemed simple, at least to me, as we sat in a room stuffed with rugs and tables and trinkets that had once furnished my family’s home in Ankara. My parents had not really assigned me an American name. They had assigned me a Turkish one deformed by unnecessary compromise. I felt, for the first time, the burden of disappointment most familiar to immigrants who, arriving overseas with so little besides their names, have to witness even those most immutable possessions stolen and remolded. Had my parents, when I was born, felt free to name me whatever they wanted, I might now be more noble (Asil), celestial (Göksel), or mighty (Kadir). To be renamed “saint,” though, is no letdown, and the easiest way to forgive a mistake is to fix it. My letter has arrived at last, signed by the judge’s pen. Now it’s official: call me Eren.

* Eren Orbey is a writer who splits his time between New Haven and Boston.