Archaeologists Home in on Homeric Clues as Turkey Declares Year of Troy

- Written by Admin TOA

- Published in Culture & Art

Photograph: DEA / M. SEEMULLER/De Agostini/Getty Images

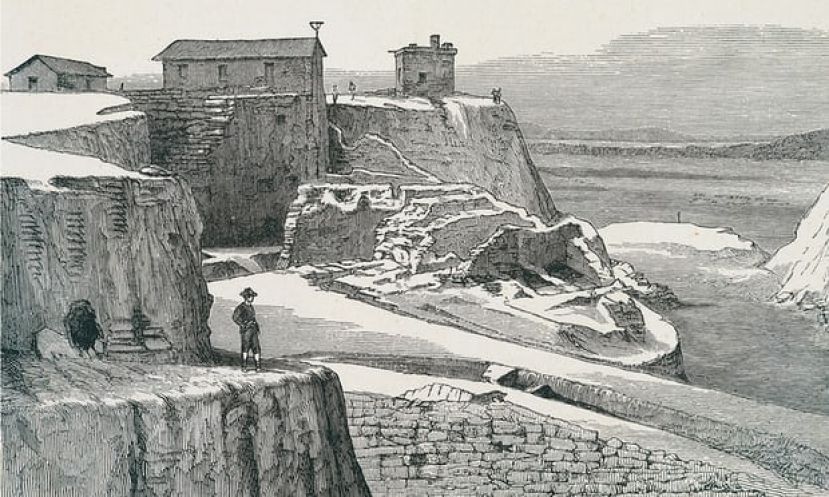

An engraving portraying the Trojan walls during Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations.

Photograph: DEA / M. SEEMULLER/De Agostini/Getty Images

An engraving portraying the Trojan walls during Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations.

Rüstem Aslan, Troy’s chief archaeologist, grows more animated as he enters the fenced-off area just beyond the southern gate of the ancient city’s ruins. To him it offers tantalising clues that may add to the evidence that this was the scene of the war detailed in Homer’s epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey. “Priam, Achilles, Hector: [whether] they lived and died here, we cannot prove that 100%,” said the affable Aslan, who started working at the site as a student in 1988. “But if you work inside for 30 years, night and day, winter or summer, surrounded by this landscape, you can feel it. You start to believe.”

The ruins of Troy are half an hour’s drive from Çanakkale, a city in north-west Turkey situated on the Dardanelles strait and near the Gallipoli peninsula. The site, on Hisarlık Hill, contains the overlapping remains of 10 cities, Troys I to X, dating from as early as 3,000BC.

Much of the excavations over the past two years have focused on an area directly across from Troy VI’s southern gate, dated to 1300BC, and the main entry into the ancient citadel from the plains below. A few dozen metres from the gate, archaeologists have uncovered a late bronze age road and the remains of a house from the era, indicating the existence of an extensive organised network of buildings beyond the city walls.

Investigations will resume in summer 2018 as Aslan and his team seek evidence of a violent confrontation in the area immediately surrounding the gate.

Archaeologists here believe Homer’s epic has a historical core that can be uncovered through excavations, a careful reading of the literature, and written documents from the Hittite empire that co-existed with Troy and collapsed with the end of the bronze age.

“This year we discovered a large area that follows from the south gate, a late bronze age street that is directly connected to the south gate, and we also found late bronze age house foundations connected to the street, which means the area around the citadel was organised and large,” Aslan says.

“Next year we will continue the excavation in an extended area and we will try to understand the last destruction layer outside the citadel. What happened, how it happened, and when it happened.”

The site was first posited as the possible scene of the war depicted in the Iliad as early as the second half of the 19th century, when excavations, first by the British consul Frank Calvert and then by a German merchant, Heinrich Schliemann, began in earnest.

Turkey hopes the accelerating work on the site will draw more tourists to the area, one of the most important historical ruins of antiquity. The country’s culture ministry has declared 2018 the year of Troy and is planning a slew of events to promote the site.

A museum will open next year housing many of the key collections and archaeological findings from the site. The Turkish government is in talks with museums around the world that have artefacts from Troy to bring them back to Turkey. The most famous is the so-called Priam’s Treasure, a collection of gold, weapons, artefacts, goblets and diadems smuggled out by Schliemann to Berlin and then taken to Moscow after the second world war, where they remain in the Pushkin Museum.

Aslan describes the Troy site when he first visited it as a student in 1988 as a “ruin of a ruin”. For him, the museum is a dream come true.

The outdoor site is kept purposely minimalist, with almost no reconstruction except for a mud-brick layer in the central fort to protect the core of old Troy from the elements. Aslan wants visitors who stand before the walls and fortifications to imagine the duel of Hector and Achilles on the grounds beyond the western gate, to see in their mind’s eye Patroclus attempting to scale the walls, or Helen and Paris surveying the assembled Greek troops on the plains below from the citadel.

An engraving portraying the Trojan walls during Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations.

He has little doubt that the multi-layered city at Hisarlık is Homer’s Troy – based on the evidence of destruction, the Hittite agreement that references King Alaksandu (who is believed to be Paris, the Trojan whose elopement with Helen, queen of Sparta, supposedly sparked the war of Greek myth) and the natural scenery that corresponds to descriptions in the legend.

Advertisement

For some, the Trojan war is not merely the foundational tale of western literature but also the foundational story of conflict between the east, symbolised by Troy and its Hittite allies, and the west, symbolised by the Aegean Greeks.

Aslan sees many lessons for today’s world. The destruction of Troy was followed by more conflict as the Hittite, Mycenaean and Egyptian empires collapsed. There were no victors in those wars – “just like the war in Syria”, across the border from Turkey, he says.

He also sees a parallel between the flight of Syrian refugees to new lands and the legend told in Virgil’s Aeneid, in which a Trojan refugee settles in the west and becomes the ancestor of the Romans.

“It’s not easy work, and you cannot prove with just architecture or archaeological objects what happened,” Aslan says of the excavations. “But we add one more piece of evidence.” ( Kareem Shaheen in Troy - www.theguardian.com)

Related items

Latest from Admin TOA

- World Energy Council Türkiye Holds the Opening Meeting of the Young Energy Leaders (YEL’26) Program

- The Shared Pulse by Eda Uzunkara

- NEO HUMAN 10.0: How Will the Future Be Shaped? (Filiz Dag)

- Calculatit.net Is Bringing Pricing Transparency to America’s Construction Industry

- Support Independent, Trustworthy Journalism